Corona take the leaders at least take

their crowns take the crowns

So that we don’t have to

How come that I felt so much more than the past years the arrival of Liberation Day, the 25th of April? How come that during this quarantine I felt so sensitive towards social struggle?

One possible answer ought to be simple and obvious: I think so because I am exposed to a new flux of emotions, a new kind of situation (a very specific one), and I would confirm that I am not just sensitive towards social struggle, but I’m more sensitive in generic terms. That would not be wrong. Yet, what sense would it have to pose a question around Liberation Day, partisans and social struggle then, rather than writing about my grown sensitivity in general?

The possible answer here, may be longer and not very linear. I think it all spouted from the death of Helin Bolek, singer of the band Grup Yorum. The 3rd of April, aged 28 (almost my age), she died after 288 days of hunger strike spent in prison, in the hospital and then at home, in Istanbul, where there are places renowned as ‘houses of Resistance’. From what I heard, these buildings sparkle with a weird kind of ghostly joy: that’s where artists die and their passion rests. Artists in life and in death, as some of Helin’s friends said about her.

And yet, I believe even before this sad and unnecessary news arrived (I don’t think we need less artists, I think we need less dictators; but surely there will be more artists thanks to Helin’s choice) I was already well-disposed to feel, to entangle with this particular topic. This takes me back to February, when my partner’s passion and policemen’s trickery (that unfolded into a trap, orchestrated inside the university of Turin by the Rector Geuna and a bunch of fascists) led her to an unfair 4-days-arrest.

Few days ago, another member of the Grup Yorum died in the unmeasurable effort of hunger strike, the bassist Mustafa Koçak. It was the day before Liberation Day in Italy. My thoughts, then, were plausibly full of their Resistance: Mustafa died after 297 days of strike, during which he refused food and medical assistance. He would weigh only 29 kilos. These numbers are like bullets in our brain: how can we even conceive putting together and grasping an adult human being into 29 kilos? And yet he was fuller than many of us.

Unpredictably (really?), I realize now that I find forms of fascism at the core of my unease. There is fascism in Erdogan’s regime. There is fascism in my partner’s arrest. There’s a lot of fascism in the history of Italian partisans. And there is a lot of fascism, we must tell, into what procured me a tough, deep, spread, knife-sharp stomach-ache the morning of the 20th of April. I woke up after 3 hours of confused sleep, when a friend from Turin called me after a few days we hadn’t been in touch. She’s putting herself in the hardest challenge to live in a precarious and yet safe berth-house, with Arab and Nigerian families (I think the metaphor between this community and a ship should be deepened). I took the call confused, a little upset because I was thinking (dreaming?) many things about political involvement and how some people in the social movements don’t know how to deal properly with political passion coming from ‘external’ activists. In my confused dreams of that night, politics were no good. No political form of politics was good at all. But I wanted to wake up by achieving the image, at least the dream of the image of the forms of the political.

As my friend called me, she woke me up, and I suddenly felt the knives cutting my stomach with an unpredictable rhythm. She understood pretty soon I could not speak, and I hope I haven’t been too rude as I later wrote her: ‘I didn’t get the meaning from this phone call’. How a common friend said, we are in a Pressure Cooker. I think she is in a Pressure Cooker more than me. The Pressure Cooker, though, is not fascism, it is the Coronavirus lockdown.

After that, I could not go back to sleep easily. Only when my father entered my room (it happens only when I’m sick) with a Chamomile infusion, I calmed down. At that time, I was in a silent delirium, but inside it was crowded with images of policemen and loud, violent, senseless screams between comrades, arguing and yelling at each other, during police operations. The day before, the 19th April, something had happened – again – in Turin (a very significant and big Pressure Cooker, in my opinion).

The trigger is ‘discretional power’: it is discretionary how and when you act in such a way that you might have to justify, but you don’t. Policemen and women (there was only one woman, actually), reacted with discretion: which means, with a ‘certain’ power. They reacted to some yelling they were receiving, after ‘taking care’ of a first arrest. It seems that in Corso Giulio Cesare, one of the most difficult and yet beautiful areas of northern Turin, a bag snatching took place, and police intervened with an iron fist. But they did not like the irony of the people shouting at them, protesting about their presumed duty to wear masks like everybody else during work-time, or about the unnecessary violence they enacted. Many things can be said from an anarchist balcony (it all happened under a palace occupied by anarchists) watching white policemen arresting non-white thieves, especially when you are locked down for weeks and your government has shown, until that point, only proofs of deceptiveness (like if an anarchist would care).

Yet, in this situation, the policemen did not think that maybe some show of protest is ‘doable’. At their own discretion, they stayed, and waited for the anarchists to walk the stairs down into the street, under their own squatted house. ‘Ask my name, and you will know anything about me without having me speaking’: that’s discretionary. What happened then is violence, verbal, physical, psychological abuse, even unconstitutional if we walk the long way around it. Once a policeman asks the identification to an anarchist, he has already called in reinforcements, three or four cars just to say, and a couple of guys from the Esercito. Once a policewoman has tried to calm you down, she says you’re leaving her no other choice, but she keeps coming towards you, with your back against the wall of your occupied house, with people screaming around you, with unmasked police forces doing the opposite of how common people should behave during quarantine. And common people, even anarchists, have to do so to respect each other (that is the naïve yet shared sense of Law – maybe the only respectful one) and the so-called public health. But police forces target you with their un-gloved hands and force you in jail, for 4 days, because you screamed at the sight of violence (just like it happened to my lover). That is discretionary. In jail without even knowing if you’re contagious or not (Le Vallette, the detention center they were brought to, is now the first prison in Italy for number of COVID cases – I wonder what a huge kind of Pressure Cooker it may be, a Pressure Cooker inside another Pressure Cooker). That’s how discretionary power works: some rules apply to some people, not to the common sense nor the police.

Many things like this happen without the need of writing a piece about it, or without them being the proper site for a lesson on the foundational violence of the modern State. But this thing happened in the Pressure Cooker, where we are right now, with police-crazy particles of air clashing, bouncing on the cooker’s walls (that look like cliffs to you) and hurting all the other particles who try to stay put (you particle, with your very heavy thinking) and still (to not let the entropy augment inside the pressure cooker). But inside the Pressure Cooker you get hurt by the police forces, using their discretionary power.

We come to the 25th of April, Liberation Day. Grup Yurum and Italian partisans in my head, I would love to get out and walk alongside my friends as well as with unknown people feeling like me. The feeling that nothing would be more important than that now, to walk in the street with a lot of people, all of us thinking of and walking towards a great set of revindications, values, and meanings of struggle. On Facebook I see my friends in Turin and in Rome reading letters in front of the commemorative plaques, bringing red flowers to the names of young boys and girls fallen against the nazi-fascists. Some of my friends have a broken voice while they borrow their bodies to remembrance. They do so at their own risk. You can see their eyes looking around, above the camera, scanning for something that could endanger them or worse, interrupt their plea of remembering the sacrificed lives of the partisans.

Scrolling down my window on the external world, the real world outside the limited outer country I’m living in during this quarantine, there it comes: another terrible news of abuse. In Milan, a little group of ‘rememberers’ has been attacked by the police. This video appears in my virtual window (the smart-phone’s screen), taken from a real window on a real street of the city: it shows people running, trying to escape this unjustified (or simply discretionary) violence. But they are grasped. One is charged and taken down to the floor, many men over just one, while a woman is hit hard on the face with an elbow strike. ‘What are you doing?’ she screams. I wonder how much of this is heard and internalized by the policeman.

I’ve always been a fan of indeterminacy: it keeps your eyes wide open to different opportunities. But it is a very ambiguous concept. Precarity is likewise. It keeps you on the verge for new uses of reality, new adaptations. But like indeterminacy, precarity is also made up by unsafety. And that is not so pleasant. Hence, I wonder, how do I feel so close to such double-faced concepts? A first achievement of writing in the Pressure Cooker may be to distinguish the precarity and indeterminacy produced by passion, from those made by the power abuses.

What does it take to be a witness, or better, is there any difference between being a witness and to witness? What if being a witness requires a distance, like the person who took on camera the violence of the police from their window in Milan, while to witness the risk of police abuse takes into account the very concreteness of being on the street? It takes a whole circle around ‘witnessing’ to put yourself in such a situation. You want to be a witness of the heroes of Resistance, so you walk down the street until the commemorative plaque, and then you witness the police abuse, while somebody is being a witness of what happens to you. And thanks to his or her video, I can feel I am a witness too. But if you die, or if you are put in a cage with no contact with the external world forever, do you stop to witness? And do I stop being a witness?

Publishing this piece of article, might be a form of being a witness, just like the person filming from the window. We do channel the nervous energy of the Pressure Cooker into writing and filming, for it makes us witnesses. But be witnessing, I think, is the first and last point of the circle, where everything ends so that it can re-start. Like a specific kind of rhythm, witnessing needs to accept the immortal passion for those who sacrificed, for what you say it’s not what they see. Witnessing may be the condition of those who want to see, but they are part of the same circle, of the same politics, of the same passion even, of those who want to tell: the witnesses will become those who will be witnessing, and it will go over and over until we will build the greatest monuments to those we are witnesses to: Partisans and Grup Yorum. We might be very skeptical about building heroes and monuments, but we will see them and tell stories about them when we witness some.

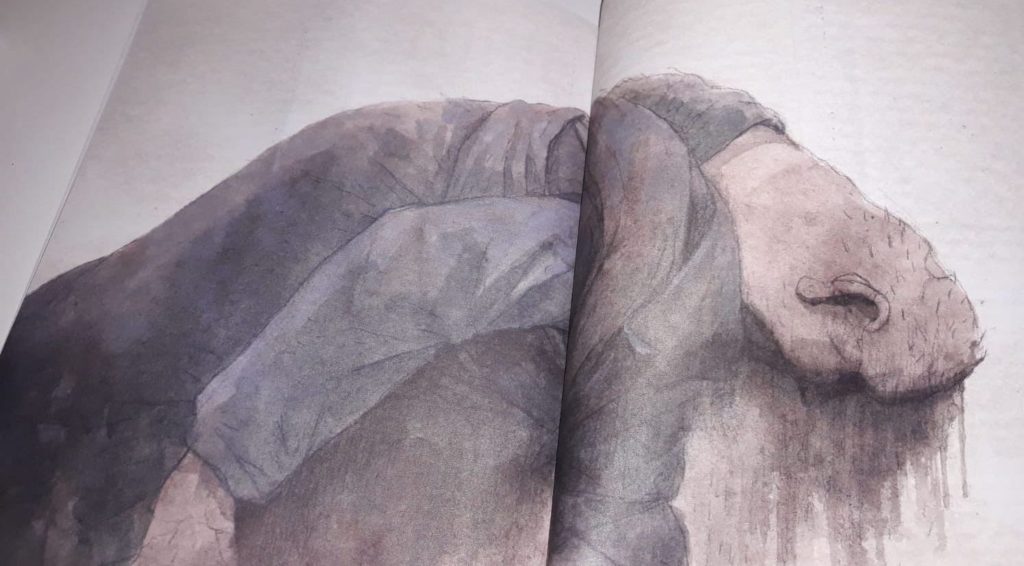

Ibrahim Gökcek pays omage to Helin Bolek

P.S.

At the present day, and this is the reason for thinking about publishing this intimate piece of writing, we happily receive from Turkish comrades the declaration of victory. Grup Yorum will be allowed again to play concerts in Turkey. The remaining Grup Yorum members in prison will be freed. Ibrahim Gökcek finally stopped the hunger strike on the 323th day of struggle.

P.P.S. the day following the announcement of this victory, Ibrahim Gökcek died in the hospital.