Stephen Muecke ha scritto questo testo durante i mesi del lockdown primaverile, e il tempo passava senza che venisse pubblicato. Per questo abbiamo deciso di tradurre la sua riflessione o il suo racconto, non facile da definire, esperimento di ficto-criticism che difficilmente trova spazio in riviste accademiche. Uno stile, o un genere per alcuni, che insieme agli argomenti di chi lo adopera interroga la forma della scrittura come linguaggio: o decisamente morto, o decisamente vivo. Tra specie compagne e distratte attenzioni, questo brano ci è sembrato appartenere alla scrittura viva: in perfetta salute!

(Original version in English below)

Durante il lockdown scopro di poter facilmente fare più cose contemporaneamente.

La mia scrivania di casa si apre in realtà multiple. La Signora Gazza viene alla mia finestra, e mangia i semi di girasole dalla mia mano[1]. Li spargo per terra e lei li prende con il suo becco inclinato su un angolo, perchè la sua mandibola superiore ha la punta rotta. Ha forse volato contro una finestra? Su uno dei miei schermi sulla scrivania, il vice Rettore sta parlando piano perchè ho abbassato il volume. Sta parlando delle opportunità legate al COVID, ma dovremo tutti lavorare duro per via della competitività. Distratto, uso l’altro mio monitor per controllare email e Facebook: un’ecologia dell’attenzione, come direbbe Yves Citton[2].

Questa ecologia incorpora la distribuzione e la distrazione nello stesso momento. Oggi, ho imparato, le merci non sono più scarse, è l’attenzione umana che è la più rara tra le risorse. Grandi quantità di danaro sono trasformate nell’arte di catturarlo. Questi giorni la Signora Gazza cattura la mia attenzione facilmente, perchè la natura, dice Mick Taussig, è diventata re-incantata in questa era di sfaldamento, un vero ‘rinascimento in auto-consapevolezza planetaria, anche se espresso in scontroso linguaggio secolare’[3]. Si riferisce alla scrittura accademica standard. Di lì l’importanza, io e lui siamo d’accordo, di cogliere onde di forza mitica usando un linguaggio maggiormente poetico, proprio come quelle pubblicità cattura-attenzione, specialmente quando usano ‘concetti che attraversano natura e cultura così facilmente’[4].

Arriva a ondate. Molte cose lo fanno. Certamente la capacità di prestare attenzione. Sto leggendo Mick Taussig che scrive il suo ‘Teatro del Sole’ in ritmi diurni, e specialmente ‘l’ora magica’ del sole albeggiante, performato con Anni Rossi al pianoforte, con tutti i suoi arpeggi. ‘Questa è la musica che firma la padronanza della non-padronanza’[5], dice.

Sono immerso nel suo libro Mastery of non-mastery mentre il vice Rettore sta tranquillamente dicendo che la nostra università provinciale è in una buona posizione, perchè la restrutturazione dell’anno passato ci ha lasciato con un banco di risorse disponibili.

Questa è una buona notizia. Nessuno sarà licenziato. Trovo di poter esser presente al suo tono, più che alle sue parole, prendendo il suo messaggio come vicino al canto della gazza. Quello che chiamiamo tono fa riferimento all’idea di Taussig dell’ ‘inconscio corporeo’, che attraversa natura e cultura, così che alla fine non sei più in grado di separare il metaforico dall’orrido perchè non c’è più natura perchè è tutta natura ora[6].

L’altro giorno la famiglia della Gazza è arrivata tutta insieme per i semi di girasole. Cantano la loro presenza con le cadenze da oboe, ed io vado alla finestra salutandole, cantando la mia canzone affettuosa. La Signora è l’unica che mangia direttamente dalla mia mano. Lo so che lei mi conosce. Il padre, Ciccio/Fatso, così lo chiamo io, mantiene la distanza. Poi c’è Junior, che di solito seguiva le loro orme squittendo con voce lamentosa, chiedendo di essere imbeccato. Alla sua età, nemmeno fosse nel nido! Ma oggi Fatso lo sposta ogni volta che prova a mangiare. E Junior cade sulla schiena, piedi all’aria, come un uccello morto dei cartoni animati. La natura che mima l’arte che imita la natura, come direbbe Taussig nella sua tesi sulla padronanza della non-padronanza. La spettacolare tattica di Junior aveva funzionato per certo: Fatso lo lasciò stare dondolando via, pensando di aver dominato la situazione.

‘Negli assemblaggi si sviluppano schemi di coordinamento non-intenzionale’, dice Anna Tsing in ‘Arts of Noticing’[7]. Penso che lei intenda agencement, come in Deleuze e Guattari, assemblaggi natural-culturali e multispecie che provocano piuttosto che significare. Questo potrebbe essere un esempio di ciò che intende: solo un paio di settimane dopo che Trump faceva il buffone in giro sparando con le sue dita ( ‘Get over here! Boom.’) parlando del massacro di Charlie Hebdo a Parigi, ad un raduno dell’NRA (National Rifle Association), ci fu un’altra sparatoria nelle scuole. Trump usa le sue dita (natura) per mimare una pistola (cultura) e la ‘coordinazione non-intenzionale’ è un’altra uccisione per emulazione. Invece di lente e creative collaborazioni, ora abbiamo PowerPoint. Taussig: ‘Il nome dice tutto’[8].

Io penso, con una memoria affettiva che vorrei mantenere per sempre, ad una intellettualità creativa con una feroce attenzione. John Berger, nel Boxing day del 2000 nel suo paese di Quincy in Haute-Savoy, ci dava forti ed enormi abbracci da orso e piccoli bicchieri di acquavite (gnole), firmando libri. Il suo descrivere, abbozzare, pensando – sempre pensando- dà attenzione intensamente senza giudicare. È come una ben calibrata attitudine etnografica, una in cui lo scrivere si aspetta di essere sorpreso da un qualche nuovo tipo di realtà: ‘… la furbizia resa dettaglio’ (dice Taussig in Palma Africana) ‘può, nell’occasione, intrufolarsi attraverso le difese che erigiamo per impedire che la realtà ci disturbi’[9]. Quindi, perchè la scrittura possa essere attenta, deve continuare ad inventare la sua stessa vulnerabilità.

Le vulnerabilità sono spazi in cui quella che chiamiamo creatività può circolare. Questa è molto diversa dall’attenzione come risorsa ‘estraibile’, dato che si può pagare per averla migliorata. La impostano come necessariamente in declino, come un problema cognitivo, come il cervello che non esegue le sue proprie ‘funzioni esecutive’: ‘Usiamo solo il 20% del nostro cervello! Con questa nuova tecnica, gente, ne puoi attivare il 50% in più…’… il venditore truffaldino delle industrie ‘psy’ unisce le forze con i mercanti di produttività di tempo e movimento, nel business senza speranza di provare a portare la gente a ‘prestare’ più attenzione all’obiettivo di estrarre valore dalle stessa nostra natura. ‘Imitando la natura al fine di sfruttarla’ [10] filtrando quello che credono essere rumore ambientale.

Economia dell’attenzione, invece che ecologia dell’attenzione. Perchè non fare un passo avanti, eliminare il sonno stesso per aumentare la produttività? Ora, dice Taussig, ‘quasi ognuno ha un ‘disturbo del sonno’, e va avanti in vite fatte di jet-lag sotto l’effetto di Ambien in insonnie neoliberali afferrando tazze di caffè fatte di polistirolo.[11]’ Ma il cosmo si dimostra resistente; potrebbe persino controbattere.

Così come la primavera arriva e i giorni si fanno più lunghi, la Signora e Fatso stanno venendo meno spesso. Forse stanno nidificando di nuovo. Junior viene da solo, ma è capriccioso mentre provo a persuaderlo a mangiare dalla mia mano. O al limite a dare una beccata. E un giorno me la da, mi becca forte sulla mano e rompe la pelle del mio palmo. C’è una goccia di sangue.

Patience si diletta nel mostrarmi il nostro giardino primaverile. ‘Guarda i germogli del nostro piccolo mandorlo!’ La montée de la sève, mi dice con un sorriso, ricordandomi del nostro tempo nel piccolo paese di Lavau della Yonne. Nella piazza del paese, le anziane signore ridacchiano della ‘ripresa della linfa’ dei loro mariti per la prima volta dopo l’inverno. È particolarmente spassoso perchè non è una metafora. Il calore sempre maggiore del sole trascina verso l’alto l’essenza sia degli uomini che degli alberi. E in un giorno di maggio, i bucaneve improvvisamente appaiono nei prati.

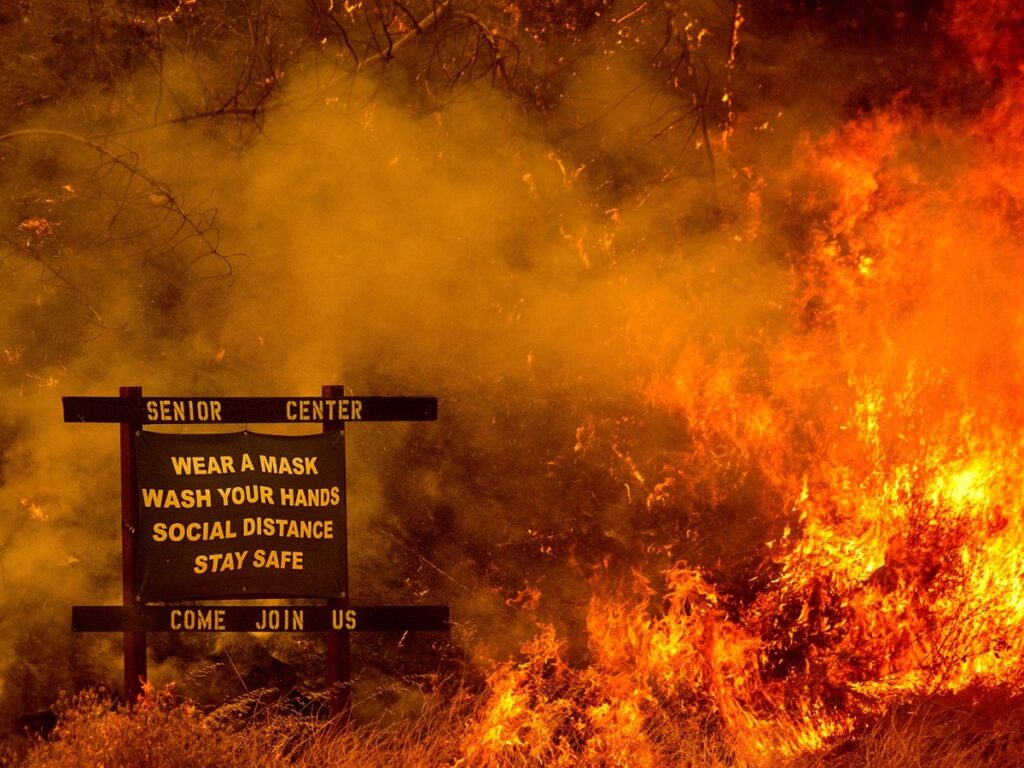

Nel frattempo patogeni killer sono in giro in cerca di opportunità. ‘… La mimesi della vita reale di insetti che si trasformano in versioni killer di sè stessi’, scrive Taussig, ‘ questi patogeni così mimeticamente furbi ingannano non solo la natura ma gli umani che pensavano di poter approfittare della dominazione ultima della natura’[12]. E il giornalista che intervista James Lovelock per the Guardian, chiede, ‘è il virus parte dell’autoregolazione di Gaia?’

(c) AP Photo/Noah Berger

‘Decisamente’, risponde Lovelock alla vigilia del suo 101esimo compleanno. ‘Questa è tutta parte dell’evoluzione per come la vide Darwin’. Tu non vedrai una nuova specie fiorire a meno che non abbia una scorta di cibo. In un certo senso è quello che stiamo diventando. Noi siamo il cibo. Potrei facilmente farti un modello e dimostrarti che così come la popolazione umana sul pianeta cresce sempre più, la probabilità dell’evoluzione di un virus che possa ridurre la popolazione è abbastanza marcata. Noi non siamo esattamente un animale desiderabile da lasciare libero in un numero illimitato sul pianeta[13]. Un paio di anni prima, Bruno Latour visitò Lovelock, poichè era entusiasta dell’ipotesi di Gaia, che lui definisce come ‘la terra, una totalità di esseri viventi e materiali che sono stati fatti insieme, non possono vivere separati, e dalla quale gli umani non possono tirarsi fuori’ [14]. Lui pensa che la teoria di Lovelock ‘detiene lo stesso posto nella storia della conoscenza umana di quella di Galileo’, nei termini in cui rivoluzionò l’ortodossia dei suoi tempi. La fisica degli oggetti di Galileo aprì l’esplorazione a un universo infinito, mentre Lovelock e Margulis hanno mostrato che viviamo in una zona critica, un sistema autoregolato di agenti costantemente in interazione, che noi stiamo ora destabilizzando. Ci potrebbe volere un po’ per portare la gente fuori dall’impostazione mentale galileiana, che ancora la fa sognare di fuggire dalla terra e colonizzare altri pianeti, allo stile della science fiction.

Speriamo di imparare qualcosa in più rispetto alle ‘arti del notare’. Questo tipo di attenzione non riguarda le relazioni tra ‘il cervello umano e il mondo lì fuori’, ma è tutta intorno l’immersione in ecologie viventi. Il popolo aborigeno con il quale ho lavorato le imparava dai propri anziani. Da bambini non erano incoraggiati a fare domande, ma solo a stare attenti. Dopo un po’ sanno. E’ un sapere-come più che una conoscenza. Quando un tracciatore aborigeno vede cose in un ambiente che il resto di noi non potrebbe notare, non è un problema di una psicologia specializzata, ma una problema di sintonizzazione intergenerazionale in un mondo particolare. Notare una cosa potrebbe anche dipendere dall’essere sintonizzati con molte altre: il sole, il vento e il modo i fringuelli si riuniscono in quella parte del paese. È un’arte, non necessariamente una individuale. Arriva a soffiate, o ad ondate. Non puoi stare in allerta tutto il tempo, nel modo in cui gli psicologi delle corporation o i neuroscienziati cognitivi vorrebbero che tu fossi, con qualche tipo di allenamento tipo neuro-crossfit, sviluppato per minimizzare la distrazione sul posto di lavoro o a scuola [15].

Il poeta coltiva arti di attenzione che sintonizzano i sè ai ritmi del corpo e dell’ambiente (avrei quasi scritto cosmici).

Provano a scrivere, poi danno un’occhiata fuori dalla finestra. Qualcosa gli viene in mente. Roland Barthes: ‘essere con qualcuno che amo e pensare a qualcos’altro: ecco come ho le mie migliori idee’ [16]. Negligente, e non distratto, si scopre essere l’opposto di attento.

Quindi, sembra che potremmo aver bisogno di entrambe, alternando attenzione e distrazione così come alterniamo l’esser svegli al dormire. Ma l’attenzione non prende solo una forma. Non è solo un meccanismo del cervello. Io penso che ci siano una serie di arti che possono essere coltivate. Quando uno studente studia per essere un biologo, impara a stare al mondo in un certo modo, discernendo il rilevante dall’irrilevante. Questa è una condizione base per la produzione di conoscenza. Se lo studente si specializza in botanica, presterà meno attenzione agli animali; la zoologa farà il contrario. Ma neanche possono permettersi di essere troppo concentrati, perchè nuova conoscenza entra dalle porte della distrazione. Isabelle Stengers ci ricorda ciò che A. N. Whitehead ha detto sulla Natura: ‘noi siamo istintivamente volenterosi di credere che grazie ad una dovuta attenzione, si può trovare di più in natura di ciò che si vede ad un primo sguardo. Ma non saremmo felici con meno.’

Quello che significa è che un buon scienziato non può rimanere con lo status quo: un zoologo, per virtù della ‘dovuta attenzione’ che applica, scoprirà una nuova specie di animali. Come potrebbe essere ‘felice con meno’? Ciò significa anche, penso, che la natura è piena di sorprese; percepire le cose che chiamiamo naturali significa essere sorpresi dai loro attributi. La natura non è solo ‘lì fuori’ in attesa di essere scoperta come è, ma sorprende in virtù dell’attenzione diretta verso di essa. La dovuta attenzione che applichiamo nelle forme d’arte, nei metodi, nei know-how. Alcune di queste sono normative, altre sono nel processo di venire dimenticate, altre ancora devono essere create, attraverso tanti campi diversi.

Sarebbe una bella correzione demografica se il virus, qualcuno sta dicendo, dovesse fare fuori tutti i Boomer, la mia generazione, quelli che avrebbero potuto fare di più per mitigare la distruzione ambientale, e invece dovranno solo scrivere ‘SCUSATECI’ scolpito sulle loro lapidi – se ne avremo una. Quasi come se Gaia stesse mettendo in atto la propria fantasia speculativa vendicandosi della mia generazione, e risparmiando figli e nipoti, facendogli portare in qualche modo un peso minore, mentre ricostruiscono – per non dire sopravvivono (a malapena).

Ma questa intelligente piccola Mietitrice non gioca pulito. Arriverà ad ondate, fino a che non ci sarà una cura. Non c’è cura. Un vaccino potrebbe prendere mesi, forse anni, per essere sviluppato e testato. I giovani possono avere ictus. Quattro giorni dopo la beccata di Junior sulla mia mano ho iniziato ad avere i brividi. Vado giù all’ambulatorio, e lì un’infermiera mi punta una pistola termometro alla testa e preme il grilletto. Faccio oltre 38. Vengo accettato in osservazione e i brividi e i dolori iniziano a contorcermi il corpo, arrivando a ondate. È estenuante; non posso nemmeno alzarmi per andare al bagno. Un catetere, molte grazie. Patience, sconvolta, non può venire a trovarmi. Mi chiama, proviamo a essere vivaci, parliamo del dopo. Provo a scherzare sugli oppiacei e il vecchio marinaio; tutte le mie battute rischiano di essere battute da papà, perdo la prospettiva. Se la tosse va peggiorando mi porteranno in un ventilatore, se ce ne è. Quale ondata è questa ora? Potrei aggiustarmi da solo il dosaggio dell’alimentazione intravenosa, mi chiedo? Nessuno può venire a trovarmi. Il dolore si abbassa; dormirò un po’, andando già come in un sogno con luci e meraviglie. Un’altra ondata.

Stephen Muecke è professore in Scrittura Creativa al College of Humanities, Arts and Social Sciences alla Flanders University, Australia del Sud.

Alex Coppel/Newspix/Getty ImagesAlex Coppel/Newspix/Getty Images (c)

[1] Gymnorhina tibicen, not related to the European magpie which is in the corvid family.

[2] Yves Citton

[3] Michael Taussig, Mastery of Non-mastery in the Age of Meltdown, (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2020), 56

[4] Taussig, Mastery of Non-mastery, 49

[5] Taussig, Mastery of Non-mastery, 171

[6] Taussig, Mastery of Non-mastery, 159

[7] Tsing 23

[8] Taussig, Mastery of Non-mastery, 41

[9] Taussig, Palma Africana, 27

[10] Taussig, Mastery of Non-mastery, 5

[11] Taussig, Mastery of Non-mastery, 160

[12] Taussig, Mastery of Non-mastery, 44-45.

[13] https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2020/jul/18/james-lovelock-the-biosphere-and-i-are-both-in-the-last-1-per-cent-of-our-lives

[14] [trans.] ‘Bruno Latour Tracks Down Gaia’, Los Angeles Review of Books, July 3rd 2018.

[15] The Distracted Mind, MIT Press[16] Roland Barthes, Pleasure of the Text, 24.

[16] Roland Barthes, Pleasure of the Text, 24.

Original version

In lockdown, I find I can multitask with ease. My home desk opens onto multiple realities. Madame Magpie comes to my window and will eat sunflower seeds from my hand.[1] I scatter them on the ground and she picks them up with her beak tilted at an angle, because her upper mandible has the tip broken off. Did she fly into a window once? On one of my desk monitors the Vice-Chancellor is speaking quietly because I have turned down the sound. He is talking about COVID-related opportunities, but we will all have to work hard because of the competition. Distracted, I use my other monitor to check email and Facebook: an ecology of attention, as Yves Citton would say.[2] This ecology incorporates distribution and distraction at the same time. Today, I learn, commodities are no longer scarce, it is human attention that is the rarest of resources. Huge amounts of money are turned into the arts of capturing it. These days Madame Magpie captures my attention easily, because nature, says Mick Taussig, has become re-enchanted in this era of meltdown, a veritable ‘renaissance in planetary self-awareness, even if couched in crabby secular language’.[3] He is referring to standard academic writing. Hence the importance, he and I agree, in catching waves of mythic force using a more poetic language, just like those attention-seeking advertisers, and especially when they use ‘concepts that cut across nature and culture so easily’.[4]

It comes in waves. Many things do. Certainly the capacity to pay attention. I’m reading Mick Taussig writing up his ‘Sun Theater’ on diurnal rhythms, and especially the ‘magic hour’ of the setting sun, performed with Anni Rossi at the piano, with all its arpeggios. ‘This is the signature music of mastery of non-mastery’, he says.[5]

I’m immersed in his Mastery of non-mastery book while the Vice-Chancellor is quietly saying that our provincial university is in a good position because last year’s restructure left us with a bank of available resources. This is good news. No-one will be retrenched. I find I can attend to his tone, more than to his words, taking his message closer to a magpie chorus. What we call tone relates to Taussig’s idea of ‘the bodily unconscious’, cutting across nature and culture, so that in the end ‘you are no longer able to separate the metaphoric from the horrific because there is no nature anymore because it’s all nature now’.[6]

The other day the Magpie family came for their sunflower seeds together. They sing their presence with their oboe cadenzas, and I come to the window, greeting them with my own sing-song affection. Madame is the only one who will eat from my hand. I know she knows me. The father, Fatso I call him, keeps his distance. Then there is Junior, who used to trail after them squeaking plaintively, asking to be beak-fed. At his age, not even in the nest! But today Fatso drives him away whenever he tries to eat. And Junior rolls over on his back, feet in the air, like a cartoon dead bird. Nature mimicking art mimicking nature, as Taussig would say in his thesis about mastery of non-mastery. Junior’s spectacular tactic certainly worked. Fatso waddled off leaving him alone, thinking he had mastered that situation.

‘Patterns of unintentional coordination develop in assemblages’, says Anna Tsing in ‘Arts of Noticing’.[7] I think she means agencement, as in Deleuze and Guattari, natural-cultural and multispecies assemblages that provoke rather than signify. This might be an example of what she means: Only a couple of weeks after Trump clowned around shooting with his fingers (‘Get over here! Boom.’) talking at an NRA rally about the Paris Charlie Hebdo massacre, there was yet another school shooting. Trump uses his fingers (nature) to mimic a gun (culture) and the ‘unintentional coordination’ is yet another ‘copy-cat’ killing. Instead of slow creative collaborations, we now have PowerPoint. Taussig: ‘The name says it all’.[8]

I think, with a fond memory that I shall retain forever, of a creative intellectual with a fierce attentiveness. John Berger, on Boxing day in 2000 in his village of Quincy in Haute-Savoie, giving us huge strong bear hugs, and signed books, and little shot glasses of gnole. His describing, sketching, thinking—always thinking—pays attention intensely without judgment. It is like a fine-tuned ethnographic attitude, one in which the writing expects to be surprised by some new kind of real: ‘…the cunningly rendered detail’ (says Taussig in Palma Africana) ‘can, on occasion, sneak through the defenses we erect so as to keep reality from disturbing us.’[9] So, for the writing to be attentive, it has to keep inventing its own vulnerability.

Vulnerabilities are spaces into which what we call creativity can flow. This is a long way from attention as a resource that can be mined, because you can pay to have it improved. They set it up as necessarily declining, as cognitive impairment, as the brain not carrying out its proper ‘executive functions’: We only use 20% of our brains! With this new technique, folks, you can mobilise 50% more … the snake-oil salesmen of the ‘psy’ industries join forces with the time and motion productivity merchants in the hopeless business of trying to get people to ‘pay’ more attention to the task of extracting value from our very natures, ‘mimicking nature so as to exploit it,’[10] while filtering out what they think is environmental noise. Attention economy, rather than attention ecology. Why not go one further, eliminate sleep itself to improve productivity? Now, says Taussig, ‘just about everyone has a “sleep disorder” and cruises through life jet-lagged on Ambien in neoliberal insomnias clutching a styrofoam coffee cup.’[11] But the cosmos is proving resistant; it may even be fighting back.

As Spring is approaching and the days are getting a bit longer, Madame and Fatso are coming less often. Perhaps they are nesting again. Junior comes on his own, but he is skittish as I try to coax him to eat out of my hand. Or at least take a peck. And then one day he does, he pecks hard and breaks the skin of my palm. There is a drop of blood.

Patience takes delight in showing me around our spring garden. ‘Look at the buds on our little almond tree!’ La montée de la sève, she says with a smile, reminding me of our time in the little village of Lavau in the Yonne. In the village square, the old ladies cackling about their husbands’ ‘rising of the sap’, for the first time after winter. It is remarkably amusing because it isn’t a metaphor. The increasing warmth of the sun draws upwards the essence of both men and trees. And on May Day snowdrops would suddenly appear in the meadows.

Meanwhile killer pathogens are out looking for opportunities. ‘…the real-life mimesis of bugs morphing into killer version of themselves’ writes Taussig, ‘such mimetically savvy pathogens fool not only nature but the humans who thought they could profit from the latest domination of nature.’[12] And the journalist interviewing James Lovelock for The Guardian, asks, ‘Is the virus part of the self-regulation of Gaia?’

‘Definitely’, replies Lovelock on the eve of his 101st birthday. ‘This is all part of evolution as Darwin saw it. You are not going to get a new species flourishing unless it has a food supply. In a sense that is what we are becoming. We are the food. I could easily make you a model and demonstrate that as the human population on the planet grew larger and larger, the probability of a virus evolving that would cut back the population is quite marked. We’re not exactly a desirable animal to let loose in unlimited numbers on the planet.’[13] A couple of years earlier, Bruno Latour paid a visit to Lovelock being enthusiastic about the Gaia hypothesis which he defines as ‘the Earth is a totality of living beings and materials that were made together, that cannot live apart, and from which humans can’t extract themselves.’[14] He thinks that Lovelock’s theory ‘holds equal place in the history of human knowledge to that of Galileo,’ in terms of revolutionising the orthodoxy of their times. Galileo’s physics of objects opened exploration into an infinite universe, while Lovelock and Margulis showed that we live in a critical zone, a self-regulating system of constantly interacting agents that we are now destabilising. It might take a while to get people out of the Galileo mindset that still has them dreaming of escaping Earth and colonising other planets, science fiction style.

Let’s hope we are learning more about the ‘arts of noticing.’ This kind of attention is not about relationships between the human brain and ‘the world out there’, but is all about immersion in living ecologies. Aboriginal people I have worked with learn about it from their elders. As children they are not encouraged to ask questions, just to be attentive. After a while they know. It is know-how more than knowledge. When an Aboriginal tracker sees things in the environment that the rest of us fail to notice, this is not a matter of a specialised psychology, but a matter of intergenerational attunement in a particular world. Noticing one thing may also depend on being attuned to many others: the sun, the wind and the way finches flock in that part of the country. It’s an art, but not necessarily an individual one. It comes in bursts, or in waves. You cannot be on the alert all the time, in the way that the corporate psychologists and cognitive neuroscientist would like you to be with some kind of ‘neuro cross-fit training’ program developed to minimise distractions in the workplace or school.[15]

The poet cultivates arts of attention which attune themselves to bodily and environmental (I almost said ‘cosmic’) rhythms. They try to write, then gaze out of the window. Something comes to them. Roland Barthes: ‘To be with the one I love and to think of something else: this is how I have my best ideas’.[16] Neglect turns out to be the opposite of attention, not distraction.

So, it seems we might need both, alternating attention and distraction like we alternate wakefulness and sleep. But attention does not just take one form. It isn’t just a brain mechanism. I think it is a set of arts that can be cultivated. When a student trains to be a biologist, they learn to attend to the world in a particular way, sorting the relevant from the irrelevant. This is a basic condition for knowledge production. If the student specialises in botany she will pay less attention to animals; the zoologist does the opposite. But they can’t afford to be too focussed because new knowledge will enter through the door of distraction. Isabelle Stengers reminds us what A. N. Whitehead said about Nature: ‘We are instinctively willing to believe that by due attention, more can be found in nature than that which is observed at first sight. But we will not be content with less.’

What this means is that good scientists can’t remain with the status quo: a zoologist, by virtue of the ‘due attention’ that she applies, will discover a new species of animal. How could she be ‘content with less’? It also means, I think, that nature is full of surprises; perceiving so-called natural things means being surprised by their attributes. Nature is not just ‘out there’ waiting to be discovered as it is, it surprises by virtue of attention directed towards it. The due attention we apply is in the form of arts, methods, and know-how. Some of these are normative, others in the process of being forgotten, and some are yet to be created, across many fields.

It would be a nice little demographic correction if the virus, as some are saying, were to take out the Boomers, my generation, the ones who could have done most to mitigate environmental destruction, and instead will just have ‘SORRY ABOUT THAT’ engraved on their headstones, if we have any. Almost as if Gaia were enacting her own speculative fantasy by taking revenge on my generation and sparing our children and grandchildren, making them carry somewhat less of a burden as they reconstruct, not to mention barely survive.

But this clever little Reaper is not playing fair. It will come in waves, until there is a cure. There is no cure. A vaccine could take months, perhaps years, to develop and test. Young people can get strokes. Four days after Junior pecked my hand I start getting the chills. I head down to Outpatients and a nurse points a thermometer gun at my head and pulls the trigger. I register over 38. I get admitted for observation and the chills and aches start to contort my body, coming in waves. It is exhausting; I can’t even get up to go to the toilet. A catheter, thanks heaps. Patience, who is distraught, can’t visit. She calls me, we try to be buoyant, we talk about afterwards. I try a joke about opiates and the ancient mariner; all my jokes threaten to be Dad jokes, I lose perspective. If the cough gets any worse they will wheel in a ventilator, if they have one. What wave is this now? Can I adjust the dosage on the intravenous feed myself, I wonder? No-one can visit. The pain subsides; I’ll just sleep a bit, going under like a dream with light and wonder. Another wave.

Stephen Muecke is Professor of Creative Writing in the College of Humanities, Arts and Social Sciences at Flinders University, South Australia, and is a Fellow of the Australian Academy of the Humanities. Recent books are Latour and the Humanities, edited with Rita Felski, Johns Hopkins University Press, 2020 and The Children’s Country: Creation of a Goolarabooloo Future in North-West Australia, co-authored with Paddy Roe, Rowman and Littlefield International 2020.